When we last spoke,

I told you I was torq-ing

this difference between

mine and manpower.

The efforts.

Because of how

when father dies

A certain kind of labour relation

goes with him.

It’s conceptual,

as much as anything,

because the labour had changed already

(and) never mine in the first.

But we long for the material, don’t we?

Some fine difference

between DAD reckoning

and DEAD reckoning

if only at the level of method.*

Film Note is Rachel O’Reilly’s first output from her ongoing artistic research project The Gas Imaginary (2014), which explores forms and norms of unconventional extraction in the area of Gladstone harbor. She started this research while travelling to Australia to visit her father during the final stages of his terminal illness. In the metaphorical but also actual sense, while her father was still alive, the eco- and human sphere were still living. Now everything has been subject to merciless capitalist extraction, till the last breath and – if possible – beyond.

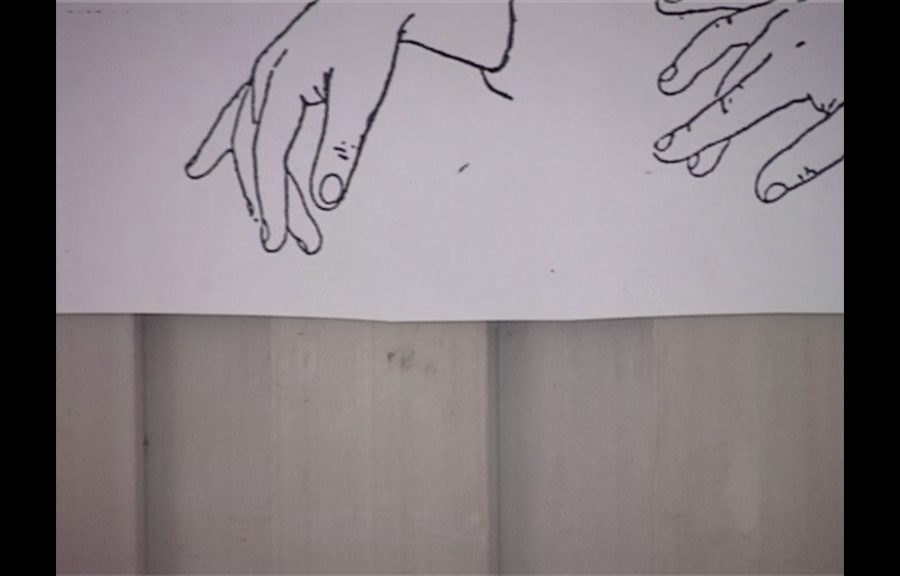

O’Reilly’s Film Note plots the story around changes in labor, living conditions, and social reproduction from the times of settler colonialism to contemporary semiocapitalism. In the historical narrative according to which industrialization in Europe initially served as a default model, the link between modernity, rationalism, and the West appeared as more than contingent. The idea of human progress followed the phases of Darwinist biological theory: from savagery through barbarism to civilization. The colonizers therefore inherited no responsibility, but were surrounded by a noisy and excessive nature – no man’s land, as they would call it.

The task of the family during the industrial epoch (famously discussed in Engels’ The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State, 1877) was to protect against the outside world and serve as a shelter from the competition of dehumanizing forces of modern society. The family as a repository for warmth and tenderness (embodied by the Mother) stood in opposition to the competitive and aggressive world of commerce (embodied by the Father). However, with the death of the Father – as O’Reilly’s Film Note explains – the compensatory and protective role of the family disappears. For this new change, O’Reilly uses the metaphor of fracking to mark the fall of modern social verticality and its replacement with a matrix of horizontal pipes – the invisible networks of power.

Gas images are made to ride on Networks,

rather than to settle here.

Each precariarizes a clearer social relation –

showing some aspect of its prior exchange.

Its the genre that communicates

even while the social license

of Corporate Citizenship

_breaks_ the civil contract.

Is it at all possible to search for the new social forms that will lead toward what Angela Davis calls “planetary belonging”?

* Rachel O’Reilly, Film Note, 2013, [excerpt from the script].

Rachel O’Reilly is an artist/poet, critic, curator, theorist and educator at the Dutch Art Institute, and a Ph.d. candidate at Goldsmiths at the Centre for Research Architecture. She was a curator at GoMA/Australian Cinémathèque and Asia Pacific Triennial and resident at Jan van Eyck Academy. Her artistic projects have been presented at Qalandiya International, IMA Brisbane, Tate Liverpool, Eflux, and Van Abbemuseum. She writes collaboratively with Jelena Vesić and Danny Butt and is part of KW production series 2019.